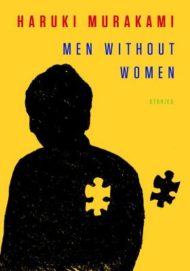

Haruki Murakami

Haruki Murakami

Translated by Philip Gabriel and Ted Goossen

Alfred A. Knopf ($25.95)

by Allan Vorda

Sometimes you come upon a writer who helps you discern some unknown world; for many readers, Haruki Murakami is such a writer. His latest creation, a collection of bizarre short stories titled Men Without Women, primarily focuses on male-female relationships, with most stories dealing with varying degrees of physical and psychological infidelity. The first two stories continue Murakami’s fondness for 1960s pop music, notably the Beatles. As he used their song “Norwegian Wood” as a novel title, Murakami here utilizes “Drive My Car” and “Yesterday” as story titles.

“Drive My Car” certainly is an apt starting point for the rest of the book. It involves a forty-seven-year-old actor named Kafuku who needs someone to drive him to work. The driver is a homely, big-breasted, chain-smoking twenty-four-year-old woman with ears “like satellite dishes” named Misaki. Initially, very little is spoken between these two insular characters, but gradually they begin to reveal themselves to each other. Kafuku tells Misaki about the affairs of his deceased wife, and how he developed a “friendship” with the fourth and last of his wife’s lovers, though he confesses that he “was acting” the whole time during their so-called friendship. However, it is the ex-lover who tells Kafuku the answer to his question about the “blind spot” Kafuku had with his wife: “If we hope to truly see another person, we have to start by looking within ourselves.”

The reader is left wondering about, and possibly hoping for, a connection between the driver and the passenger, since they both seem disconnected from reality. As in Murakami’s acclaimed 2014 novel Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage, there is no final resolution. Perhaps the Beatles song offers some promise: “I got no car and it’s breaking my heart, / but I found a driver and that’s a start.”

Many of the stories explore the vagaries of connection. “Yesterday” is about a young man named Kitaru who asks his best friend to date his girlfriend, a test of both love and friendship. “An Independent Organ” focuses on a fifty-one-year-old plastic surgeon who has countless affairs until he finally falls in love—except the women he loves is in love with someone else, so he slowly starves himself to death. “Scheherazade,” a weird variation on A Thousand and One Nights, features a housekeeper who tells sexually inflected stories after making love to the homeowner, and “Samsa in Love,” a take-off on Kafka’s Metamorphosis, is simply too strange to describe.

“Kino” might be the best of the seven stories here; it features a jazz bar owner who has recently discovered his wife was having an affair. (Murakami, it should be noted, owned a jazz bar called Peter Cat before becoming a full-time writer.) The story opens with Kino (which translates in Japanese to “yesterday”) talking to a visitor named Kamita (translates to “god’s field”). Strange characters enter—a mysterious visitor, a femme fatale, a gray cat, and a bluish snake, about which Kino learns: “If you want to kill that snake, you need to go to its hideout when it’s not there, locate the beating heart, and cut it in two.” As the surreal noir hurtles toward the ending, the reader is left trying to figure out the connection between all of the characters, and what it all means.

The last tale is the title story, which begins with a phone call at 1:00 AM when a man calls to say his wife has committed suicide; the caller hangs up without identifying himself, leaving the narrator to wonder who the woman is. He believes she is a woman, M, he broke up with years ago; it so happens M is the third woman he has dated that has killed herself, and as he reminisces about her, fact and fantasy blur. “Truthfully, I like to think of M as a girl I met when she was fourteen. That didn’t actually happen, but here, at least, I’d like to imagine it did.” At the end of his imagistic wanderings, the narrator declares how everything has vanished for him: “All that remains is an old broken piece of eraser, and the far-off sound of the sailors’ dirge. And the unicorn beside the fountain, his lonely horn aimed at the sky.” As with the other stories in Men Without Women, much is left for the reader to decipher.

And perhaps that’s the point. Murakami makes readers wonder thanks to his unique ability to include “movement in and out of the protagonist’s inner mind” (as Matthew Carl Strecher wrote in his 2014 book The Forbidden Worlds of Haruki Murakami); he has infused these seven hypnotically bizarre stories of broken and twisted relationships into something both magical and Kafkaesque. I wonder if the late Junichiro Tanizaki, one of Japan’s greatest novelists, ever thought another Japanese writer could write anything stranger than as The Secret History of the Lord of Musashi. Read Men Without Women and decide.