Laurence A. Rickels

Laurence A. Rickels

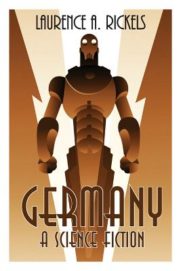

Anti-Oedipus Press ($19.95)

by Andrew Marzoni

That Bob Arctor—an undercover narcotics agent known to his employers as “Fred” and addicted to Substance-D, a drug referred to by its users as “Death”—begins to hear imaginary radio transmissions of Goethe’s Faust should signal to readers of Philip K. Dick’s 1977 novel A Scanner Darkly that the protagonist is losing his mind, the effects of the drug widening the schizophrenic gap between his two identities: “Was grinsest du mir, hohler Schädel, her?” Why grinnest thou at me, thou hollow skull? Surely, there are thematic parallels in both Dick’s and Goethe’s tragedies about men who sought too much knowledge, but Laurence A. Rickels would have you believe that this mysterious appearance of German Romanticism in postwar California signifies much more.

Though Rickels doesn’t discuss A Scanner Darkly in his latest book, Germany: A Science Fiction (he may have exhausted the subject in 2010’s I Think I Am: Philip K. Dick), Dick is among several Californian science fiction pioneers—Robert Heinlein, Thomas Pynchon, Walt Disney—in whose work Rickels sees the return of the genre’s repressed: Nazism, the Holocaust, and the V-2 rocket. It might not be the case that fascism, genocide, and war were ever absent from sci-fi––or as Rickels prefers, “psy-fi,” roping the work of Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung, Melanie Klein, and D.W. Winnicott in with the genre—nor that Dick, Pynchon, Heinlein, or Disney are cryptofascists (some more than others). Rather, Rickels argues, “Because Nazi Germany appeared so closely associated with specific science fictions as their realization, after WWII the genre had to delete the recent past and begin again with the new Cold War opposition,” eventually becoming “native to the Cold War habitat.” Rickels’s study thus “addresses the syndications of the missing era in the science fiction mainstream, the phantasmagoria of its returns, and the extent of the integration of all the above since some point in the 1980s.”

The unrelentingly dense academese of Rickels’s prose is worth noting if only because it is impossible to ignore. Combining the psychoanalytic vocabulary of Jacques Lacan with the deconstructive methods of Jacques Derrida, Rickels arrives at a deconstruction of psychoanalysis not unlike the “schizoanalysis” of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari (Germany: A Science Fiction is published by Anti-Oedipus Press, whose name references Deleuze and Guattari’s landmark 1977 collaboration). At its best, Rickels’s prose is a vehicle of pithy brilliance: comparing Ellie (Jodi Foster) in Robert Zemeckis’s Contact (1997) to Christine in Gaston Leroux’s The Phantom of the Opera (1910), Rickels writes that the two women “projected a communications network for contact with the other side, which the father’s departure could then carry forward. One young woman’s opera singing career under the missing father’s aegis is another woman’s professional commitment to the exploration of Outer Space.” Rickels is adept at the art of plot-summary-as-psychoanalysis, and he can be quite funny: at one point, he critiques Friedrich Kittler’s critique of Laurence Rickels. But at its worst, Rickels’s prose is infuriatingly obscure, the stuff of graduate student nightmares: “The columbarium of remembrance is instead streamlined for life’s transmission.” One wonders at times if Rickels’s intended audience is perhaps even smaller than what his tiny independent publisher is able to afford.

It is admittedly unfair to judge Rickels too harshly for his erudition, as he appears to be on to something here. He provides a convincing history of the Third Reich’s rebirth in California from V-2 inventor Wernher von Braun’s televised collaborations with Disney in the 1950s through Dick’s breakthrough alternate history, The Man in the High Castle (1962), and Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow (1973). Rickels is not the only writer to identify California as the site of a renaissance in German late modernism: in his 2008 Weimar on the Pacific, Erhard Bahr documents the emigré Los Angeles of Thomas Mann, Bertolt Brecht, Fritz Lang, and Theodor Adorno, and Herbert Marcuse’s Frankfurt-School-in-exile received a satirical treatment in Joel and Ethan Coen’s recent Hail, Caesar! (2016). In 1975, Lester Bangs began his Creem profile of Kraftwerk by citing the influence of methamphetamine (a German invention) on postwar American counterculture to argue that “the Reich never died, it just reincarnated in American archetypes ground out by holloweyed jerkyfingered mannikins locked into their typewriters and guitars like rhinoceroses copulating.” Adam Curtis’s 2002 study The Century of the Self shows how the public relations industry, that cornerstone of Hollywood, was born from the manipulations of Viennese psychoanalysis by Freud’s nephew, Edward Bernays. In books like The Case of California (1991) and Nazi Psychoanalysis (2002), and in academic posts at UC Santa Barbara and the Academy of Fine Arts, Karlsruhe, Rickels has been writing about and living in Germany and California for three decades. His geographic determinism makes it difficult not to read Germany: A Science Fiction as an intellectual autobiography—a summation of his career as a psychoanalyst, a teacher of comparative literature, and a reader of science fiction, arguing frantically and encyclopedically that these diverse fields constitute, in the end, the same thing.

Rickels’s skill as a close reader is what makes Germany: A Science Fiction most compelling, such as when he illustrates the transposed negotiation of Cold War politics by means of both World War II and the American Civil War in deep cuts like Heinlein’s 1964 novel Farnham’s Freehold. But Rickels’s broader arguments about transatlantic exchange are limited by his adherence to psychoanalytic frames of understanding. The echoes of fascism in the Auschwitz-like work camp where the newly “rehabilitated” Arctor finds himself at the end of A Scanner Darkly seem not to require the discourses on mourning and melancholia projected by Rickels in order to be rendered legible.