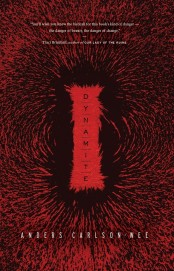

Anders Carlson-Wee

Anders Carlson-Wee

Bull City Press ($12)

by J.G. McClure

It’s a good year for Anders Carlson-Wee. The co-star of the 2015 Napa Film Festival-selected documentary Riding the Highline (directed by his brother Kai Carlson-Wee) won the Frost Place Chapbook Competition with his debut Dynamite. The chapbook’s opening poem, “Dynamite,” establishes the collection’s tone:

My brother hits me hard with a stick

so I whip a choke-chainacross his face. We’re playing

a game called Dynamitewhere everything you throw

is a stick of dynamite,unless it’s pine. Pine sticks

are rifles and pinecones are grenades,but everything else is dynamite.

There’s much to praise in the opening of this poem: the forceful, direct language and skillful enjambments come to mind. But perhaps the most admirable aspect of this opening passage is the way it treats the violent and arbitrary rules of this “game” as immutable facts. By doing so, Carlson-Wee pulls us into the poem’s universe and makes us accept its laws. As the poem continues, however, it complicates that universe: amidst all the blood, there’s also a strange tenderness. When the poem reaches its final couplet—“I say a hammer isn’t dynamite. / He reminds me that everything is dynamite”—the speaker wants out of the inexorable rules of the game, and we do too. But both we and the speaker understand that to get out is impossible. It’s a wonderfully understated and chilling ending that follows, surprising and inevitable, from the stanzas that precede it.

The jagged blend of violence and tenderness that makes up the titular poem is a definitive feature of Dynamite, and it’s a blend that Carlson-Wee’s work inhabits well. Take the opening of “Gathering Firewood on Tinpan”:

I bundle them against my chest, not sure

if they’re dry enough. Gauging how long

they’ll keep me warm by the thickness.

I step around carefully, looking for the deadest,

searching the low places

for something small and old that will catch.

I pick up the dander loosened

as my father folds his hands, lowers his head.

The rolling thunder on the surface of a nail.

I pick up the cross that seesaws his chest

with each step. The day I lost my faith.

The night my dog ran away and came back sick.

The battery-pump of her final breath.

As in “Dynamite,” the opening movements of the poem work well to establish the universe in which it exists. Again we see that mix of tenderness and destruction, and we’re primed to read it (and the speaker’s urgent cold) into his reflections on the deaths of his father and dog. The staccato delivery of each gesture makes us feel as if we’re getting the speaker’s immediate thoughts in the moment. The poem continues:

Still wondering if she left alone,

or if my father walked her out of this world.

Still wondering what he used for a leash.

I go further into the trees and find

more fuel. My friends faded on oxy

and percocet. My cousin Scott

buried young in the floodplain.

My brother and the ways I burden him.

The image of the father walking the dog “out of this world” would seem maudlin in the hands of a less skilled poet, but Carlson-Wee’s strangely practical lyricism offsets sentimentality and points us back to the moment and its violence: this time, the harm that the speaker’s friends and family inflict on themselves, using drugs that are meant to alleviate harm, which carries over into “my brother and the ways I burden him.” It’s a devastating line made all the more forceful by its simplicity. The poem concludes:

Living it over and over each night.

My father walking into every dream.

My fire not bright enough to reveal anything.

Not even his face. Not even the leash.

Carlson-Wee achieves here a more honest version of Keats’s Negative Capability—the speaker stands before the mystery he knows he cannot answer—but still he wants an answer, and sees his inability to find one (that “fire not bright enough to reveal anything”) as a failure. That moving and all-too-human frustration wonderfully informs the penultimate sentence and its irony—as if to see and know the faces of the dead is the least we could ask for. But the real gut-punch comes in the final short sentence; the poem’s return to the seemingly forgotten line about the “leash” makes this ending land perfectly.

2015 Frost Place judge Jennifer Grotz writes that “Dynamite is a collection that first affects the reader strongly and swiftly—and then achingly and hauntingly over time.” She’s right: the more time I spend with these poems, the more I admire them. At only twenty-seven pages, you can read this collection quickly—but I’m not sure you’ll ever be finished with it.