Eric Allen Hall

Eric Allen Hall

Johns Hopkins University Press ($34.95)

by Andrew Cleary

Watching politics without understanding the rules of the game is like watching a sporting event without any knowledge of its rules or traditions: it may seem to be a competition of some sort, but there is no way to know who is competing with whom over what. As with sports, large segments of the population have no emotional investment in these ongoing political competitions and manage quite well in life without paying any attention to who is winning or losing.

—W. Russell Neuman, The Paradox of Mass Politics

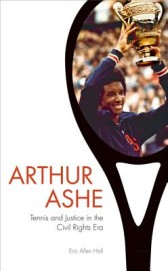

Neuman’s words may explain why it can take the work of a historian to tell how a man like Arthur Ashe could come to change the rules of the games—politics and sports—that ruled his life. Eric Allen Hall’s biography of Ashe is assiduous in giving context, ever-traceable in its sources, to the tennis player’s life: his childhood in segregated Richmond is recounted with a summary of how de jure segregation ruled the lives of American children; his coming of age as an athlete and ROTC member includes sketches of the Civil Rights Era on campus and in Vietnam; his ascendance to a globe-touring professional with public demonstrations against apartheid in South Africa includes glosses on the competitive structure of world tennis and the Cold War arrangement of power between the segregated nations of America and South Africa.

Ashe was not the first black athlete to compete in professional tennis, nor the first to win a Grand Slam title. In both cases the first was Althea Gibson, who won the U.S. Nationals a decade before Ashe won it in its rebranded U.S. Open form (and who went on to a successful professional golf career after her retirement from tennis). Both Gibson and Ashe were coached by Dr. Robert Walter Johnson, who, as Hall explains, encouraged all players under his tutelage to follow in Jackie Robinson’s footsteps:

Johnson knew that Jackie Robinson’s ascension to Major League Baseball had as much to do with his temperament as with his athletic abilities. Beaned, spiked, and taunted by racially motivated bench jockeyers, Robinson remained calm and composed, allowing his bat and feet to do the talking. . . . “His assumption,” Ashe wrote of Johnson in his diary, “was that if you wanted to get into a poker game, and there was only one game in town, you had better learn to play by the prevailing rules at that table.”

As Jackie Robinson pointed out in I Never Had It Made, this display of what Hall elides as “temperament” was a profound struggle to perform as “the image of the patient black freak,” inured to degradation from public policy on high down to the lowest dugout chatter. Temperament for an individual may work something like how James Baldwin described culture for a group of people: “not a community basket-weaving project, nor yet an act of God . . . [but] nothing more or less than the recorded and visible effects on a body of people of the vicissitudes with which they had been forced to deal.”

After winning the U.S. Open in 1968, Ashe began a years-long public and private struggle against South African apartheid. He applied for a visa to compete in the South African Open, and was promptly rejected. He signed on to a public call for sanctions against South Africa. When his world tennis ranking slipped from second to eighth and he failed to make the finals of the 1969 U.S. Open, French Open, Australian Open, or Wimbledon, Ashe was called on to answer charges that his “off-the-court issues” were depressing his athletic performance. “I must try as far as possible,” Ashe told the Los Angeles Times, “to shut out everything but tennis. But, of course, I can’t shut out the color issue. I think about it all the time . . . Is it possible to be a tennis player first and a black man second[?] It has to be. If I put the priorities the other way round I’ll be a poor tennis player and therefore a less effective black man.”

In 2014, Jason Collins played the last months of his professional basketball career after publicly coming out as gay. In announcing his retirement the following fall, Collins reflected on his earlier dread of coming out and being tarred with “the dreaded D word” as an excuse for teams not to hire him. “You know what a real distraction is? Maintaining a lie 24 hours a day, seven days a week, for most of your career, for most of your life. The energy involved in hiding the stress, shame, and fear of being gay is a full-time job. With all that removed, I was like a new person.”

This may echo Baldwin: “It is part of the price the Negro pays for his position in this society that, as Richard Wright points out, he is almost always acting. A Negro learns to gauge precisely what reaction the alien person facing him desires, and he produces it with disarming artlessness.” And it may be considered progress of some kind that the dissembling that has exhausted Collins is that which has guarded his sexuality, rather than that which forced Ashe and Robinson to fit their full personalities through the keyhole that American society allowed for black athletes to enter professional sports.

Or perhaps the mask fit better for Ashe, who by Hall’s account was as much a reserved intellectual as he was an explosive tennis player. As a teenager, Ashe first began to receive national attention for his wins in junior tournaments, like the National Interscholastic Championships in Charlottesville, Virginia, where Ashe won the 1961 final in straight sets. “Of course,” Ashe later recalled, “there was a great deal of fuss about being the ‘first black’ . . . to win at Charlottesville, etc. Those comments always put me under pressure to justify my accomplishments on racial grounds, as if sports were the cutting edge of our nation’s move toward improved race relations.”

In the decades since Robinson’s death, Major League Baseball has integrated to something approaching parity with wider American demographics, as just over 7% of players in 2012 were black, compared to 13% of the overall population. The league, meanwhile, has embraced the late pioneer, subsuming his persona into its ongoing campaign to identify the business interests of a multibillion-dollar corporation with a pageantry of American tradition, racial progress, and military parade. For his part, Arthur Ashe’s name graces the tennis center that hosts the U.S. Open; that tournament has seen no African-American male champion since, though Serena and Venus Williams have each taken the title twice.

It remains to be seen whether the example of players like Collins or Michael Sam, who in 2014 was the first openly gay player to be drafted by the National Football League, will have such effect on their sports as that of Gibson, Ashe, and Robinson. The legacy of the earlier players may still speak through the fact that neither Collins or Sam, players of color themselves, needed to perform as doubly best in sport and personal conduct in order to play professional sports. May it also not require the work of such careful scholars as Hall to recover their humanity from their symbolic status,